To view our Privacy Policy please click below

Supporting the North West Centre for Heart & Lung Transplantation

Graham Brushett

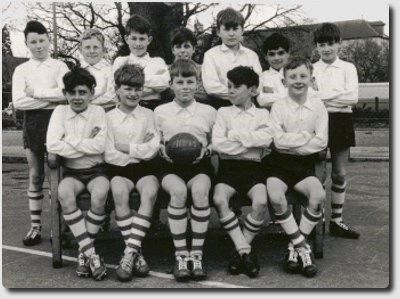

Don’t little boys love their sport? They certainly did where I was brought up in the 1960’s. The photo shows me as the third lad from the left on the back row. I was a very keen member of the Summerbee Junior School football team based in Bournemouth. This photo was taken the year before England won the World Cup. All the boys in the photo wanted to play for England.

In fact I remember that we all competed in just about every type of sport. The same boys made up the cricket team, swam for the school and took part in athletics events. My parents wished I spent less time competing at sport and more time studying like my two sisters. Typical male stereotype! I left the junior school in the same year the 11-plus entry exam was scrapped in Bournemouth. This was a stroke of good fortune because I probably would have failed it.

So how does an active young lad turn into this very ill person pictured below 41 years later? There were no early signs that such a transformation was going to occur. That is why I am sharing my journey to a transplant with you. I would have taken the very complacent view as a young person that I would never need hospital treatment, let alone a heart and kidney transplant. This is a perfectly natural reaction for a young person to take. We all believe ourselves to be invulnerable at that age.

The photo above was taken on January 1st, 2006. I had been given a very rare weekend out from Salford Royal, where I was on dialysis, to visit my family in Bournemouth. It was the last time I saw my mother whose life was rapidly taken by pancreatic cancer. She died whilst I was still in Intensive Care getting over my transplant operation. That made the whole experience for me a very bitter-sweet one. It was unbelievable to get through such a major operation after being so ill, but not to be around to a support my mother was a great sadness. My life promoting experience will always be over-shadowed by the fact that a young 15 year old boy died and his family gifted his organs to me.

I feel so sad for the family that lost their son so that I could be with mine. Deceased donation will always be fraught for those that agree to donation and for those that receive the gift of life. There are huge mixed emotions involved. There is the guilt I feel for the donor family and the other patients that have died waiting for the same organs. I have immense gratitude towards the donor family which can never be fully expressed. I am definitely angry with my own body for letting me down so badly! I thought I had looked after it pretty well! I will always be amazed at a health service that kept battling to keep me alive. There has been regret for the experience that my family and friends had to endure watching me nearly die on several occasions. The whole journey is like a manic emotional rollercoaster.

The Slippery Slope to a Transplant

It transpires that my journey into a transplant probably started at birth back in 1955. Not until the mid 1990’s was I diagnosed with Desmin Storage Myopathy, a pretty rare inherited muscle wasting condition. I showed no symptoms of any problems until I was sixteen. I had trials to play professional football but we found that my heart was enlarged and distended. Dr Conway at Southampton General hospital recommended an 18 month break from sport. An earth shattering blow for a ‘sportaholic’ such as myself. Soccer ambitions disappeared over night. The imposed ‘holiday’ from sport allowed the heart to reduce back to a normal shape and size, but probably the damage had already been done.

The same problem came back to haunt me when I had been accepted for the graduate entry scheme to join the West Midlands Police Force in 1976 pending a medical test. The test shed light on a suspected heart murmur. “Thank you, but no thank you” came the response from the police. This set back came at the end of my degree course at Birmingham University in 1976. Eventaully I took my teaching qualifications after a spell working for Austin Rover during the period of its rapid decline – purely coincidence I hope. I took up my first teaching post in Bolton in August 1983.

A month after my son was born in 1993 and the day after another exhausting squash match I felt a little ’faint’ walking to my classroom to teach another session of ‘A’ level Government & Politics. Maybe it was the thought of explaining to a group of 17 year old students how Margaret Thatcher had transformed British politics in the 1980’s that affected my metabolism? By 6pm I was sent by erstwhile GP, Dr Martin, to Bury General Hospital.

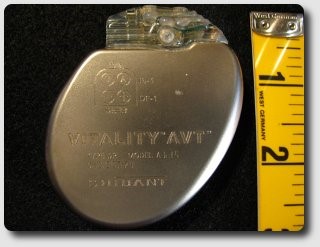

“You have experienced brady-tachy cardia young man – a pacemaker will sort you out”. Great. Throw in a few more terms like atrial flutter, sick sinus syndrome and arrhythmia alongside a load of nasty medication and you end up with a very distressed wife coping with a young baby and a patient that cannot believe what is happening to him!

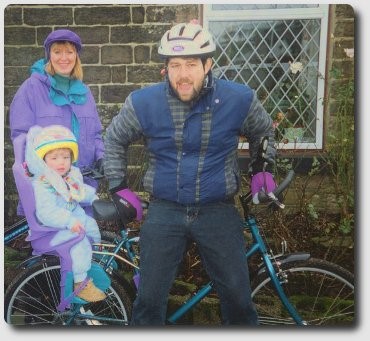

Dr Bennett’s pacemaker installation at Wythenshawe and an ablation allowed normal service to be resumed. He fitted a dual chamber, demand pacemaker. A few pacemaker models later Dr Shearer accepted that my tiredness and lethargy required further investigation. The pacing was doing its job. Something else had to be considered. So despite the best efforts of the electrical box of tricks that I was presented with over the years the lethargy and tiredness could not be shaken off. In fact it gradually got worse. Despite this life continued much the same, but everything was much harder worker – teaching, being a dad and a husband. The cycle photo is taken in 1994 a year after the first pacemaker was installed. We have loads of hills where we live to the north of Bolton – so the fitness must have been pretty good at that stage.

Desmin Storage Myopathy

Enter Dr Hilton-Jones in Oxford. “You have Desmin Storage Myopathy – probably an inherited muscle disorder that is causing your muscles to weaken.” Nice one. This diagnosis made the picture more complex. Was the heart condition purely electrical or were other factors limiting its output?

Cutting a very long story short let’s skip to heart failure and left systolic dysfunction. Simply expressed this is when the heart is beating like mad to achieve very little oxygen output, as measured by the ejection fraction. The left ventricle in a healthy heart pumps out about 60% of its oxygenated blood supply to keep the body going. In my case it fell to less than 10%. The Heart Failure clinic at Wythenshawe helped to support my heart with medication. I was placed in the very capable hands of Dr Brooks and Sister Coppinger, who still regards me as one of her ‘failures’ because I went on to need a heart transplant! She overlooks the fact that her efforts kept me alive in the intervening period. The heart failure forces the heart to work harder and sets up a vicious circle. The muscle wall of the heart gets bigger as its pumping action gets less effective, so the wall thickens and pumps less oxygenated blood to the body and so on.

But what do I know? I’m only the patient. Let’s keep it simple….I am diagnosed with cardiomyopathy.

Insufficient oxygenated blood getting round your body is going to cause problems eventually, despite medical intervention. Give up sport, retire from work aged 47 and slowly recede into a shell. Family life become very reclusive – immense stresses and strains take their emotional and psychological toll on all of us. A busy husband and father turns into a bed ridden shadow. Not quite what you hoped from life.

Cardiomyopathy

The transformation in lifestyle is very difficult for anyone to accept when a health condition has such a marked impact on your own life and that of your family. Hopes and aspirations have to be redefined – ambitions and goals lessened to accommodate the reality of the circumstances. It takes its toll emotionally on all involved. Survival becomes the order of the day with a desire to be rescued. There is a strong human need to be rescued from such situations and those that love you want to rescue you. My heart had changed from the one to the left of the photo to an enlarged one unable to support me. Sorry if the photo is putting you off your tea – I’m not too sure why the Finnish Chief Medical Examiner decided to have this shot taken – but it illustrates perfectly what cardiomyopathy can do to a healthy heart, irrespective of life style, age, ethnicity or gender. Unlike kidneys the healthy heart can only be donated if the donor has died on a ventilator and has been diagnosed as brain stem dead. That is the bitter-sweet experience of a heart transplant. My life depended on someone else’s life ending in a very particluar way. In the UK fewer than 1% of people die in a manner that would enable hearts, lungs, livers and kidneys to be donated. In the year I needed a heart & kidney transplant there were fewer than 600 potential donors. Not all of these donors had ‘suitable’ hearts – perhaps they were damaged in some way, or the blood and tissue type did not match mine. Some of the hearts would have been the wrong size which is a crucial factor for heart transplants. Sometimes the heart cannot be retrieved quickly enough or it deteriorates too fast so that it cannot be transplanted. Occasionally families refuse consent for the heart to be retrieved but allow other organs to be used. With so few donor opportunities I am extremely lucky to be here.

Most of 2004 and 2005 was spent either in Fairfield Hospital in Bury, the Royal Salford or at Wythenshawe. Congested heart failure leads to the body retaining fluid. Huge problems with oedema left me in ward F5 at Wythenshawe for more weeks than the staff would like to remember! Mind you they sold a lot of tickets to view the naked night time walks that I took in my sleep – or is that a myth they made up? Evidently I would walk around the ward at night naked pinching shoes belonging to other patients. One poor man found an extra person alongside him – it was me! I stalked the wards looking for my wife. What a pain I must have been – the power of medication is what I blame it on! The experience was prolonged and often distressing. Cardiac wards can bring rapid success and recovery for patients needing by-pass stents. For others no medical solution is available. Watching people die is a painful experience for the families and the staff that have provided dedicated support. It is a very sobering experience for the patient waiting for a heart transplant. One nurse explained to me that the desperately needed organs might arrive by helicopter. Long days were spent looking out of the window for the arrival of the life saving transport.

Dr Nick Brooks and Dr Petra Jenkins listed me for a heart transplant in August 2005. Forty days later I had a stroke. Dr Roberts my neurologist calls it an ‘oxygen dump’. Not enough oxygen getting round the body has potentially fatal consequences. I had eaten. Limited oxygen supply goes to the digestive system. The brain gets starved of oxygen – I go deaf, blind and ‘gaga’. I went into the nonsense gabble talk that is experienced by people who have a stroke. Fortunately the sight gets switched back on and one ear decides to play again. The balance remains impaired. Some say I am still ‘gaga’.

At this point you get taken off the transplant list because I became medically too unstable. Fifty days later on my wedding anniversary in October 2005 an embolism to my right kidney leaves me with no renal function and a scary visit to Wythenshawe’s intensive care unit. The heart is a powerful force in our bodies. If it gives out signs of failure other parts will come out in sympathy. This became the most stressful period of all. Could I be relisted for a transplant? No longer was it just a heart issue. My neurologist Dr Mark Roberts had to discuss why the stroke had occurred with the heart team that included the Director of Transplants, Nazir Yonan, and cardiologist Simon Williams. The renal doctors (Venning, Shurrab & Riad) then had to decide whether a kidney transplant was feasible and whether or not I could be relisted for a double transplant. Things were not looking too good. If only I had received my heart within 40 days of being listed. But that’s life ….. full of buts, ifs and maybes! After much discussion between various teams of medics I was relisted for the double organ transplant in February 2006.

Dialysis

Dr Venning and Michelle Murphy got me accustomed to life on dialysis at Wythenshawe – a very dodgy experience if you have heart failure. They helped to restore my creatinine levels to a point where a double transplant could be justified, before my lung function became too weak. I was switched to ward G2 at Royal Salford and dialysed until my first transplant call at the beginning of June 2006.

For those of you not familiar with the challenge of dialysis let me tell you it is best to be avoided. RRT (renal replacement therapy) is designed to cleanse the blood. Each day our bodies fill with toxins and fluids that efficient kidneys filter out of our system. If the kidneys fail dialysis becomes an artificial, mechanical substitute – it does not cure the condition – it manages it. Leading renal surgeons argue very forcefully that increased life expectancy and improved quality of life can only be achieved for patients with renal failure by having a kidney transplants at the earliest opportunity. In fact some doctors recommend a transplant from a well matched living donor BEFORE going onto to dialysis. Life expectancy is increased significantly by taking this drastic step. Why is this step ‘drastic’? To guarantee a pre-dialysis kidney transplant you need a relative with two healthy kidneys that is willing to share one with you. It is a great deal to ask of a relative – but over 800 such transplants take place each year in the UK and this figure will continue to grow.

You can imagine that in my position, with a seriously weak heart, dialysis was a gruelling experience made all the more difficult demanding by the death of friends going through the same process. That is why I want to make the transplant process more transparent through increased education. There is no need for people to die waiting for a transplant, yet I have known too many people that have. ONE PERSON IS TOO MANY. Why does society choose to burn or bury life saving tissue and organs instead of donate them to rescue people’s lives?

My first call for a transplant happened late at night which is fairly typical for major transplant surgery. Operating staff and theatre time become available after the routine, elective surgery of the day time schedule has been completed. With my bag already packed and suitably shattered after another long session on dialysis my wife and I drove to the transplant clinic. Gill was very stressed by the whole experience. I think I just wanted the team to get on with the job. I was convinced I was in very safe hands which included Colin Campbell (surgeon) and the coordinator team led by Jane Nuttall on that night. I cannot imagine the stress a family goes through to be called repeatedly. I know of one lung patient that was called ELEVEN times before he was successful. Tragically some patients are never called – they die.

My transplant team at Wythenshawe had been told that a matching heart and kidney had been found from the same donor in Scotland. The blood type, size and tissue match looked good I was assured. They were safely on their way from Edinburgh by plane.

Guess what, the plane carrying the organs wouldn’t take off from Scotland. By the time alternative transport could be arranged the heart would have been useless for me. The heart has a cold ischaemic time of less than 5 hours. This means the amount of time it can be out of the donor’s body, pumped with saline solution and reduced to about 4 degrees centigrade to keep it viable. Beyond this time span there is a high risk of damage to the heart. I am pleased to say that the mitral valves from the heart went to other patients and the kidney was not wasted. But I fear that a person waiting further down the queue for a heart may have died because of this transport failure.

So I woke up the following morning, having been fully prepped for the operation, to find my old heart still struggling away.

A lot of people were very disappointed to see me back on dialysis – none more so than me! But this treatment had to continue until a second call arrived. Remarkably it came within a fortnight. The window of opportunity came twice in quick succession. I was still desperate for a double transplant yet strong enough to hopefully get through the operation. That is the balancing act that medical teams have to get right. They juggle with the fact that they cannot ‘waste’ a precious organ on someone that can survive without it, but if they leave the operation too long the patient may die because at the crucial moment a matching organ is not available. Who would be a surgeon?

The Second Call

The second call for a transplant again took place late at night. Again it was after a dialysis session at Salford. This time the coordinator team was led by Helen Newton and the man that replaced my heart was Nizar Yonan. It was only after the operation was successfully completed that I was told that the organs had come by road from the North East of England. Nobody wanted to tempt fate a second time! I am told the heart procedure went well. I was left with my new heart to prove it could keep me alive for a few hours before the kidney transplant team came over from Manchester Royal Infirmary. Ravi Pararajahsingham completed the kidney procedure.

The photo above shows me being interviewed by Matt O’Donoghue for Granada Reports as part of the National Transplant Week campaign. Fortunately for me Nazir Yonan did all the talking on my behalf – it’s very hard to have a meaningful conversation with a tracheostomy tube in your chest! The short news item tracked my progress before and after the operation.

Systemic bleeding meant that I had a long stay in intensive care fully sedated after the 14 hour operation. Not only did I receive two organs from a complete stranger but also five whole bodies worth of blood. I needed platelets by the bucket load. So I am hugely indebted to all the A positive blood donors in the North West that made my recovery possible. It is a very strange feeling to be walking about with other people’s blood cells inside you! The long spell in intensive care came with the consolation that I did not have to watch England’s dismal performance in the World Cup. I think I woke up just at the point that Zinedine Zidane was sent off in the World Cup final on July 9th. A very surreal experience. A very hot summer came to end when I was finally allowed home on August 12th 2006 to rebuild a life with my family that had so nearly been lost.

The collaboration of many people has enabled me to get to where I am. Paramedics, volunteer drivers, ambulance drivers and porters have shunted me miles around different hospitals. Too many technicians to mention have analysed most of my body fluids. No ‘oscopy’ has been missed. Hundreds of scans and X-rays have been done. Phlebotomists have probably taken from me more blood to examine than the 50 units I was given to get through my 14 hour operation. Social workers and psychologists have played their part too over a 5 year period of really deep depression leading up to my transplant. To be told that you are going to die without a life saving transplant inevitably creates a few unusual stresses and strains, especially for a person that had been so active in earlier years.

I have so many people to thank at the Jim Quick ward, the teams of coordinators at Manchester and Newcastle, the New Start team, the army of NHS administrators and a very special modest carer I call ‘Gertie’. All the canteen staff that have fed me – let me recommend the breakfast at Salford and the Coronation chicken sandwiches in ward F5 at Wythenshawe. Hundreds of nurses and auxiliaries from all around the world have fed me, washed me and given me hope. I have been treated and cared for by people from Iraq, Iran, Spain, Ireland, Germany, Russia, India, Egypt, Scotland, Wales, Indonesia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, China, the Caribbean and South Africa. And a few from England! The NHS is the third largest global employer. Thanks too to the cleaners that come round every day giving words of encouragement as they go about their vital tasks. The physios & dieticians that make you wonder if all the process was worth it! They remind you that only half the job is done and that much more hard work is to follow if full recovery is to be made. The punch line is quite simple – “comply or die”. In simple terms this means:

Keep active – try to maintain as much physical activity as possible to keep muscles working, especially if serious muscle degradation has occurred surrounding the time of the surgery – as it did in my case. Prolonged periods of lying in hospital beds is great for losing weight but you also lose a lot of muscle bulk which can only be rebuilt with a lot of effort.

Follow all your medication guidelines – in my case this means taking 19 tablets a day. The critical drugs are the immunosuppressants which hopefully will minimise the risk of organ rejection. Other drugs reduce blood pressure, control cholesterol levels, and guard against the risk of gout, calcium enrichment tablets and so on.

Watch your diet – avoid non-pasteurised foods that may contain bacteria that could be disastrous for people with suppressed immune systems. Sea food and soft cheeses should be avoided for this reason. Try to keep the waist line slim to avoid unnecessary strain on the heart and limit the impact of diabetes.

A by-product of transplantation and its medication can be the increased risk of type two diabetes, (sometimes known as late on-set diabetes).

The risk of getting certain types of cancer will also increase after a transplant – particularly skin cancer. So extra precautions have to be taken in terms of guarding against the impact of the sun and UVB rays.

Fluid intake: drink a lot of clean water and keep alcohol to a minimum.

Avoid certain fruits like grapefruit because they can interfere with your drug regimen.

Try to keep your brain active! It is very common to go into a steep depression post transplant. This is sometimes described as a form of post traumatic stress. There is the real challenge of rebuilding a meaningful life after the operation especially if your previous life style cannot be resurrected. The setting of achievable goals along with exercise requires a lot of discipline, but it has to be done. Otherwise what is the point of going through the trauma of major transplant surgery? But it is not always easy.

My limited effort to support the transplant process is my way of repaying the huge debt that I owe to society, my family, the NHS and my donor and his family. Most of all I want as many people as possible to enjoy the second chance of life that I have been given. Transplants genuinely do save lives, money and misery – we just need more of them. That is why I have set up this website to help people gain a deeper insight into the transplant process and to encourage colleges to use these materials with their students. I totally endorse the principal aim of the Organ Donation Taskforce which is to make transplants a normal part of hospital activity available to all. To achieve this goal significant changes in cultural attitudes amongst the public as a whole and health professionals in particular have to continue the momentum started by the Taskforce. The Taskforce recommendations must be the catalyst for change. This opportunity for saving more lives must not be lost. If Dteg can play a small part in this process my transplant will have achieved something.

The Good

& The Ugly